Lots for drivers and teams to learn at Indy Open Test

The run plan for a team at the annual pre-Indianapolis 500 test is fairly standard. Drivers are asked to assess a range of ride height (...)

The run plan for a team at the annual pre-Indianapolis 500 test is fairly standard. Drivers are asked to assess a range of ride height changes, suspension adjustments to things like camber and toe, and downforce settings during group outings and solo qualifying simulations.

A change is made, the driver heads out for a few laps to get a read and return to give their opinion — while their engineers look through the onboard data –before moving onto the next change. That routine will happen a dozen times or more on a typical test day as ideas are tried and knowledge is gained.

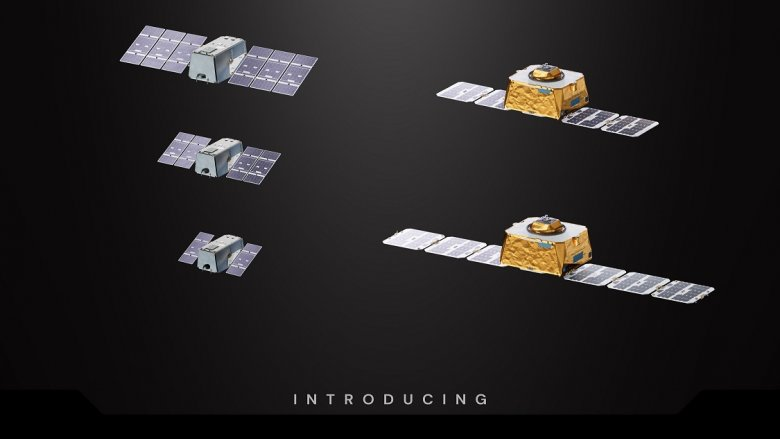

But there’s nothing typical about what will take place during this week’s Wednesday-Thursday test at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Thanks to the introduction of hybridization with energy recovery systems last summer, 12 teams and 34 drivers will make use of the two-day Speedway visit to learn about something entirely new — at least on the big 2.5-mile oval in a full-field setting — while developing the best practices to harvest and deploy horsepower from the ERS units.

Select drivers got to sample hybridization at an IMS tire test late last year, but the Open Test is where everyone, from rookies to veterans, will get to focus on tuning their cars in traditional ways and delve into the unique strategies involved with capturing electronic horsepower on an oval. Team Penske’s Ben Bretzman, winner of the Indy 500 in 2019 with Simon Pagenaud and polesitter last year with Scott McLaughlin, is expecting a hectic 48 hours of information gathering during the test. It will happen in stages with lower practice/race turbo boost on Wednesday, a shift to higher qualifying boost Thursday morning, and a return to race boost in the afternoon to close the test.

“There’s a massive distinction between what qualifying is with the hybrid versus how you’re going to use it in the race,” Bretzman told RACER. “So trying to separate those two is the first thing we have to do. Qualifying is its own separate beast and with Indianapolis being the world’s largest dyno, you have to really understand the efficiency of the hybrid, when you regen, and how you regen during qualifying.

“For the race, it’s a whole ‘nother story. You’ve got traffic, you’ve got a lot of gear shifting, a lot of being on the rev limiter and a lot of leading, right? And a lot of fuel save. How do you bring the hybrid into all this? You can use the hybrid to regen in the draft. We all know that, but there is an art to passing cars at Indianapolis — your momentum, and how you use that momentum. And how do you use the hybrid to manage your gaps and your approach to passing a car?

“And then, do you use it when you’re leading or not? What do you do when you’re trying to save fuel in the middle of the race, because that’s the section when the pace really slows down and everybody starts worrying about fuel. Do you use it to supplement things there? There’s a lot to think about and a lot to figure out. I think on the race side, there’s way more to it than the qualifying side.”

The complex and competing demands of race day bring more permutations into calculating the best use of the hybrid system. Josh Tons/Lumen

The complex and competing demands of race day bring more permutations into calculating the best use of the hybrid system. Josh Tons/Lumen

The sheer size of IMS changes how IndyCar’s hybrid system will be used. Outside of Indy, the act of braking is where the ERS comes to life and does most of the work to charge itself while the car is slowing. Charging is essentially free under braking because it doesn’t hurt lap times or lap speeds.

At Indy, harvesting will come at a cost to performance in some scenarios because it happens while accelerating.

Braking is rarely done at the Speedway in an IndyCar, so an electronic workaround was devised that replicates the effects of charging while braking, all without the need to touch the brake pedal.

To harvest energy and fill up the battery with approximately 60hp to use on demand, drivers use their steering wheels where a button is pushed, or a lever is pulled to tell the ERS units to kick in and recharge while flying down the straights. There’s also an automated harvesting option that can be enabled by their engine suppliers.

The Speedway version of harvesting is a gentler, less abrupt version of road course harvesting, but it’s still an electronic form of slowing the car. Once harvesting starts, the ERS uses the input shaft, which connects the turbo V6 Chevy and Honda engines to the transmissions, to spin hard and charge. But using the input shaft to harvest means some drag — mechanical resistance — is applied, and as a result, an engine singing at that 12,000 RPM redline might dip to 11,700, or lower, while straight-line harvesting is engaged. Even if it’s miniscule, there’s no escaping the fact that Speedway charging pulls the powertrain down while harvesting between Turns 4-1 and Turns 2-3.

The negative effects of charging can be nullified in a good draft that lifts the engines back up to their redline, but there’s no drafting while running solo during those four laps of qualifying to set the grid.

Cars will head out to qualify for the big race with their batteries fully charged, but will anyone try to harvest and risk losing speed? Or is there a positive tradeoff to by charging each lap and stacking another 60hp on top of what the high-boost Chevys and Hondas will make?

Look for some teams to try both options during qualifying simulations to quantify the gains and losses.

“You’re obviously taking power away to regen,” Bretzman said. “It’s a tricky conversation, because you’ve got four laps in qualifying and obviously you’ve got this button that gives you more power. When do you want to use it vs engine temperatures? When do you want to use it vs tire degradation. And then, do you actually want to charge it back up or not?

“Do you want to lose power to charge it back up? To get that power back at some point, there’s going to be a loss in the system, right? Because you’re running alone, no draft to mask the loss. So, how do you want to manage that? There’s a lot of things to try to understand, and there’s some windows where you can try to figure out what the most efficient process is there.”

Lots to keep track of — and even more to think about. Joe Skibinski/IMS Photo

Lots to keep track of — and even more to think about. Joe Skibinski/IMS Photo

On top of making history next month with the running of the first hybrid Indy 500, Bretzman expects the 109th edition of “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing” to break new mental and physical ground with the 33 drivers.

With all the lap-by-lap adjustments drivers already make in the cockpit with anti-roll bar adjustments, weight-jacker changes, engine setting modifications on the steering wheel, along with the shifting and turning and managing a range of other parameters, harvesting, deploying, and tuning hybrid settings on the wheel will make for 500 headache-inducing miles of frenzied activities in the cockpit. Throw in the actual wheel-to-wheel racing, and drivers are facing their busiest Indy 500.

“This is going to be a great preview with the drivers to get them comfortable and confident with what they’re doing,” Bretzman said. “Once you’re used to it, it’ll be easier, but there’s still scenarios that are going to pop up all through the month of May that everybody’s got to figure out how to manage. There’s a lot to the racecraft side of it.

“The drivers are going to be very, very busy between shifting gears and managing their gaps, managing the draft and then managing their weight jackers and their hybrid regens and their deploys and trying to save fuel. So that’s the biggest thing you can get out of the hybrid time in this Open Test. Preview this stuff now so they are better prepared for it when we come back in May.”