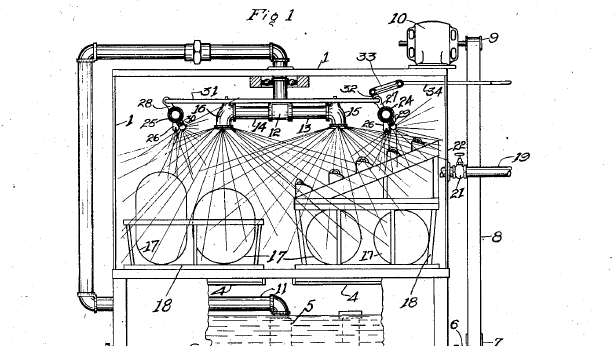

Josephine Cochrane Invented the Modern Dishwasher — In 1886

Popular Science has an excellent article on how Josephine Cochrane transformed how dishes are cleaned by inventing an automated dish washing machine and obtaining a patent in 1886. Dishwashers had …read more

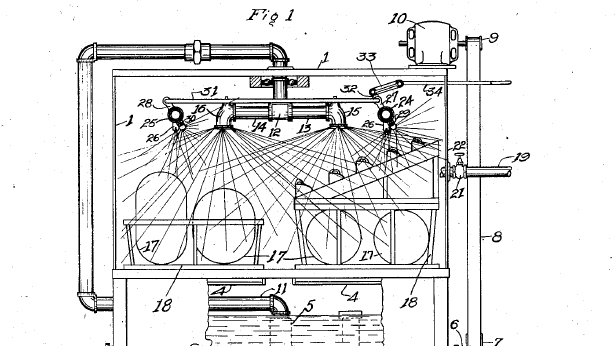

Popular Science has an excellent article on how Josephine Cochrane transformed how dishes are cleaned by inventing an automated dish washing machine and obtaining a patent in 1886. Dishwashers had been attempted before, but hers was the first with the revolutionary idea of using water pressure to clean dishes placed in wire racks, rather than relying on some sort of physical scrubber. The very first KitchenAid household dishwashers were based on her machines, making modern dishwashers direct descendants of her original design.

It wasn’t an overnight success. Josephine faced many hurdles. Saying it was difficult for a woman to start a venture or do business during this period of history doesn’t do justice to just how many barriers existed, even discounting the fact that her late husband was something we would today recognize as a violent alcoholic. One who left her little money and many debts upon his death, to boot.

She was nevertheless able to focus on developing her machine, and eventually hired mechanic George Butters to help create a prototype. The two of them working in near secrecy because a man being seen regularly visiting her home was simply asking for trouble. Then there were all the challenges of launching a product in a business world that had little place for a woman. One can sense the weight of it all in a quote from Josephine (shared in a write-up by the USPTO) in which she says “If I knew all I know today when I began to put the dishwasher on the market, I never would have had the courage to start.”

But Josephine persevered and her invention made a stir at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, winning an award and mesmerizing onlookers. Not only was it invented by a woman, but her dishwashers were used by restaurants on-site to clean tens of thousands of dishes, day in and day out. Her marvelous machine was not yet a household device, but restaurants, hotels, colleges, and hospitals all saw the benefits and lined up to place orders.

Early machines were highly effective, but they were not the affordable, standard household appliances they are today. There certainly existed a household demand for her machine — dishwashing was a tedious chore that no one enjoyed — but household dishwashing was a task primarily done by women. Women did not control purchasing decisions, and it was difficult for men of the time (who did not spend theirs washing dishes) to be motivated about the benefits. The device was expensive, but it did away with a tremendous amount of labor. Surely the price was justified? Yet women themselves — the ones who would benefit the most — were often not on board. Josephine reflected that many women did not yet seem to think of their own time and comfort as having intrinsic value.

Josephine Cochrane ran a highly successful business and continued to refine her designs. She died in 1913 and it wasn’t until the 1950s that dishwashers — direct descendants of her original design — truly started to become popular with the general public.

Nowadays, dishwashers are such a solved problem that not only are they a feature in an instructive engineering story, but we rarely see anyone building one (though it has happened.)

We have Josephine Cochrane to thank for that. Not just her intellect and ingenuity in coming up with it, but the fact that she persevered enough to bring her creation over the finish line.

![[Quinn Dunki] Makes a Screw Shortener Fit for Kings](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/let-s-make-a-screw-shortener-plca-flylua-webm-shot0001_featured.png?#)