From the new RACER magazine: Monaco, California

Well, kinda… 50 years ago, California unveiled its harborfront street race, and while perhaps less glamorous than Monaco, the birth (...)

Well, kinda… 50 years ago, California unveiled its harborfront street race, and while perhaps less glamorous than Monaco, the birth of the Grand Prix of Long Beach is no less extraordinary.

When a pack of Formula 5000 cars bellowed into life on Friday, Sept. 26, 1975, somewhere around 1:15pm PT, then rumbled out of the pits to embark on their 80-second, 90mph route around the streets of downtown Long Beach, it was the penultimate step in a dream sequence initiated, devised and delivered by California-based Englishman, Chris Pook.

The growl of those 302cu.in Chevys (and a couple of Dodges) rattled the glass of pawnshops and (somewhat disguised) porn shops, and by the end of Sunday, a run-down Southern California city whose main claims to fame had been harboring a 40-year-old ocean liner and building brand-new airliners now also had itself an auto race. This noisy curio, not quite in the shadow of the Queen Mary and not quite under the flightpath of McDonnell Douglas, attracted 65,000 people over the three days, according to the media. And this was a mere curtain-raiser. In six months, the same temporary track would host the third round of the 1976 Formula 1 World Championship.

Pook had moved to Southern California in 1963, and by ’73 was a high-flying travel agent, with the accounts of the San Diego Chargers, California (now LA) Angels, Oakland Athletics and LA Sharks sports franchises. And when he also landed the account for the Long Beach Convention and Visitors Bureau (LBCVB), he swiftly learned that the city was in need of a major boost.

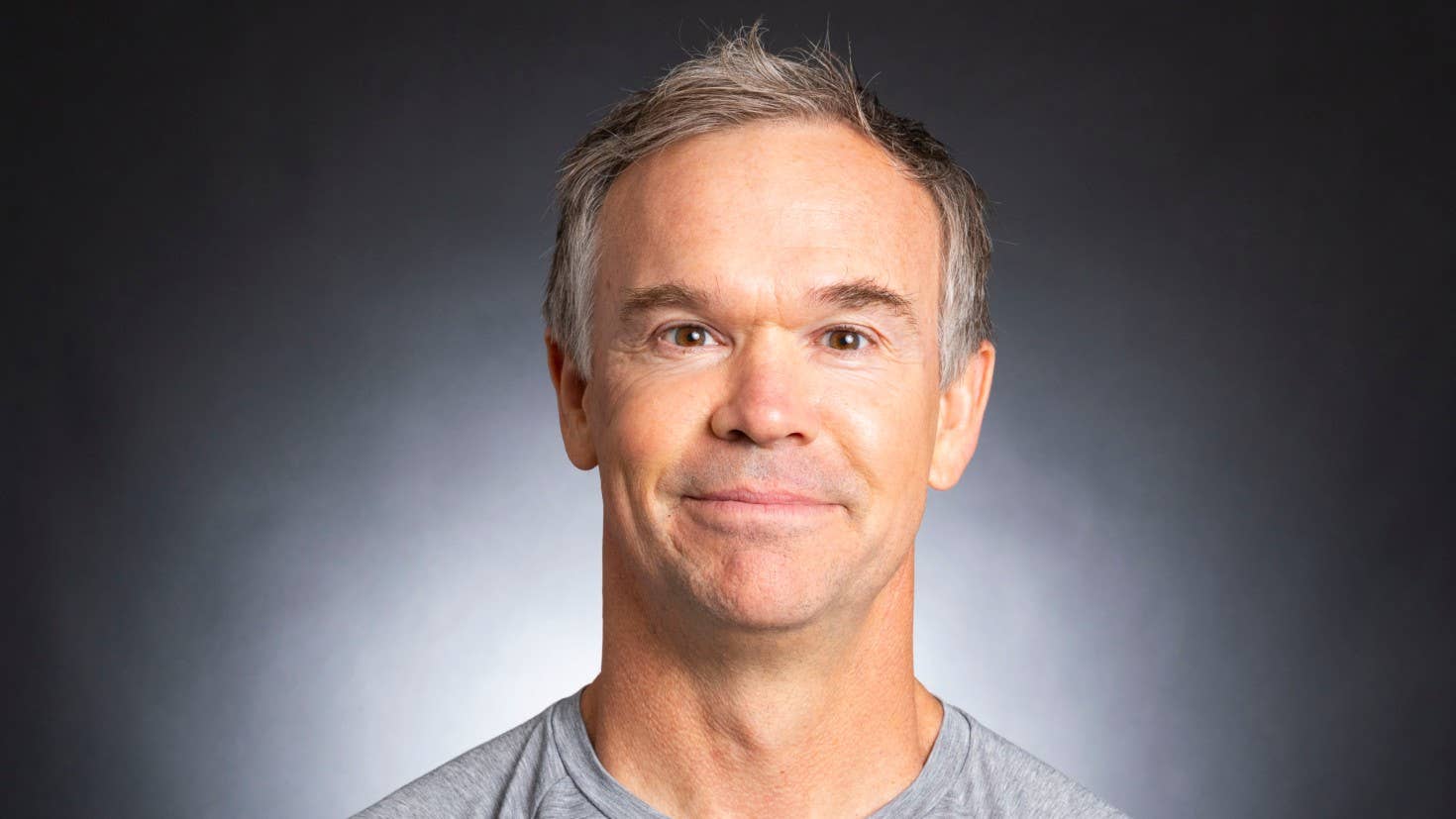

“Long Beach was in trouble in the late ’60s and early ’70s,” says Pook (above). “Having lost its oil revenues, it decided to become a tourist and convention destination. The problem was that it had no decent quality hotels. It had motels for the Navy and ship-building boys, but that was it.

“I said to the LBCVB guys, ‘It’s going to take you years to establish this as a trade show and convention area. You’re a hidden destination.’ They agreed and asked what could be done, and I said, ‘You need to do something outrageous like Monte Carlo did to compete with Nice and Cannes: they came up with the Monaco Grand Prix. Why don’t you just copy them?!’ And the long and the short of it, that’s how the race came about.”

If that was a wild idea, Pook was also a realist: to get people even vaguely interested, he would need support from someone with the credibility and status to make skeptics listen. So he approached Dan Gurney, only recently retired from driving and neck-deep in team ownership and overseeing engineering at his All American Racers outfit. Pook couldn’t have picked a more suitable figure: of course the ever-adventurous Dan was intrigued by the idea of a SoCal street race.

A chapter of Gurney’s as yet unpublished autobiography, “The Passion of Former Days,” written with his wife Evi, is dedicated to the Grand Prix of Long Beach’s origins. The late legend recalled telling Pook, “It’s bold, it’s risky, it will probably never happen, but I like it, I like it a lot. Damn the torpedoes, let’s go full steam ahead like in the pioneer days!”

He went on: “I asked for a legal opinion from my attorneys… They wrote a letter back, outlining the pros and cons, ending with the sentence, ‘Considering all the facts, we cannot recommend your involvement.’ Evi has reminded me through the years that I read this letter to her in my office, then tore it up…while lamenting the lack of courage, vision and pioneering spirit in our country.

“To me, a race through a city was not a lunatic idea as some characterized it, but maybe exactly the right and innovative thing to shake up the establishment and capture the hearts and imagination of racing fans worldwide. We were businessmen, but we still had a soul and a bit of romanticism in our DNA. To try and create something against all odds appealed to my nature.”

Gurney was so enthusiastic that on his and Pook’s first meeting with the LBCVB, he designed the course, which they later drove to confirm its viability.

Wrote Gurney: “Considering the layout of the city, it was very important in my view to make Ocean Blvd. the long main straight of the circuit. We’d make the two shorter sections downhill on Linden and uphill on Pine Street part of the track as well. These two sections proved to be spectacular, praised by drivers and spectators alike. To see an F1 car racing there at speed, sliding sideways down the hill, remains etched in my memory as an unforgettable experience.”

Gurney would recruit Les Richter, the former LA Rams linebacker who’d been running Riverside International Raceway since 1959, to provide advice and impetus when tackling city councilors, who were initially among the skeptics. But Pook really started to believe the event was going to happen when Gurney got Tom Binford onboard.

“Tom was chairman of ACCUS ,” says Pook, “and they were the liaison between the FIA and the U.S. racing scene. He came out here with Dr. Nino Bacciagaluppi, who was operations director at Monza and chairman of the safety commission; when they got excited, the project really gained momentum. That was the summer of ’74. I’m not saying all the hurdles had been jumped and all the red tape cut through, but that was when it really felt we had the right people on our side.”

One of those hurdles was that new F1 tracks needed to be at least 2.5 miles long, and Gurney’s Long Beach layout for Long Beach was 2.02 miles, but Monaco, too, was barely more than two miles in length, which cooled that potential hot potato.

Also, any new track on the F1 calendar needed to be proven viable by running another professional race beforehand. Again, no problem: both the SCCA and USAC were supportive, and their headline act, F5000, would prove ideal as a headliner in ’75. Then, in late ’74, Gurney drove one of his F5000 Eagles up a closed stretch of Shoreline Drive to pass the decibel test. All good.

The necessary pieces seemed to be clicking into place. Even when the relationship with Richter soured and he quit his role as director of racing, Gurney was able to replace him with 1961 F1 world champion and three-time Le Mans winner Phil Hill!

“That said, it was honestly touch and go until about July 1975, when we got clearance from the Coastal Commission for the race to go ahead,” notes Pook. Which is partly why, in the last couple of months before the inaugural race, the Grand Prix Association of Long Beach was still scrambling to get everything ready. But, gradually and/or suddenly, the grandstands, concrete blocks, catchfencing and tire walls were set in place. A little more than three hours behind schedule, Vern Schuppan in Gurney’s gorgeous Jorgensen Eagle led the F5000 field out on track for practice on that historic Friday afternoon.

On Saturday, Mario Andretti took pole ahead of his Vel’s Parnelli Jones teammate, Al Unser, with Tony Brise third for Theodore Racing ahead of the Shadow-Dodges of Jackie Oliver and Tom Pryce. Given that 44 cars had entered, heat races were necessary to determine the 28 starters for Sunday’s main event. In Heat 1, Brise’s Lola led home Andretti’s similar car and Pryce, while Unser beat Brian Redman’s Carl Haas-run Lola and Hogan Racing duo Jody Scheckter and David Hobbs in Heat 2.

The following day Gurney, Phil Hill, Graham Hill and Bob Bondurant ran demo laps in Toyota Celicas before the serious business began. Al Unser, Andretti and Brise all took turns leading the F5000 race, but each fell by the wayside, opening the door for Redman to win by a half minute from Schuppan.

Meanwhile, Pook could breathe a sigh of relief: the first Grand Prix of Long Beach was in the books, but he had learned several lessons, the most important of which was, “Never ever run an event like that off of my radio! Going forward, I would have a gameplan, and over the winter of ’75/’76, I developed a literal minute-by-minute schedule that answered all the countless questions I’d been asked over my walkie-talkie during race weekend. It’s generally not the racing that causes headaches; it’s all the peripheral stuff.”

In which case, Pook gave himself a few more headaches, because that “peripheral stuff” was embellished beyond measure the following March: he had to make a big first impression on the F1 circus. On the Tuesday before the inaugural U.S. Grand Prix West (to distinguish it from the U.S. GP at Watkins Glen), the cars were parked on Pine Avenue as if at a concours display, accompanied by team members with whom the public were allowed to mingle, and pose with cars and their drivers. Come the weekend, there were parachutists, drag boat displays, a Toyota celebrity race, motorcycle stunt teams, and flypasts. And the historic F1 race featured Juan Manuel Fangio, Gurney, Sir Stirling Moss, Sir Jack Brabham, Phil Hill, Denny Hulme, Richie Ginther, Innes Ireland, Rene Dreyfus and Carroll Shelby. Dan won in a BRM.

After a weekend like that, it hardly mattered that Clay Regazzoni’s Ferrari left everyone behind and dominated the headlining F1 race, leading home defending world champion Niki Lauda in a Ferrari 1-2. In the event’s infancy, the sight and sound of powerful open-wheel race cars howling and slithering through the streets of a slightly shabby port city in Los Angeles County may have still seemed incongruous, but it was spectacular.

And by then – in fact, after the 1975 F5000 race – Pook had a Bernie Ecclestone-signed contract in his pocket for at least three editions of the U.S. Grand Prix West. In ’77, the first year of the event being sponsored by Toyota, Mario Andretti won, and in the words of Pook, “the event took on a life of its own.”

There have been circuit layout changes; there were switches from F1 to CART Indy cars, and then from CART/Champ Car to IndyCar; Jim Michaelian, the original CFO, took over from Pook as CEO of the GPALB; Toyota withdrew after 40-plus years and was replaced by Acura; and 2020 saw an enforced sabbatical for the event due to restrictions around the COVID-19 pandemic. But a half century after its first edition, the Grand Prix of Long Beach remains North America’s greatest, biggest street race.

As Gurney (above) wrote in 2016, “It has been very gratifying for me to hear many young people say they got hooked on motor racing because of Long Beach… Now when I look out of the window from the Hyatt Hotel and see the changed landscape of the city, the skyscrapers and the aquarium, the white sails in the marina and the many new restaurants and hotels, it fills my heart with great pride that a motor race played a part in this transformation. I am proud that we were risk takers.”

And we are grateful still.

Reset. Restart. Those are the underlying themes of the latest issue of RACER magazine, The New Challenges Issue. We’ve always celebrated the spectacle – the color, the speed and the drama – showcased the stars and cars, and told the stories that take you inside the sport, but now we’re delivering it in a bigger, better and more vibrant way. With its stunning photography, leading-edge design and engaging writing, RACER’s been leading the field since 1992, and now we’re elevating the magazine experience once again.

CLICK HERE to purchase the new issue of RACER. And to have the new-look RACER magazine delivered to your mailbox six times per year, CLICK HERE to check out print and digital subscription options.