Build a high-performance Brainf**k JIT and AOT compiler on top of C# type system

What is Brainfuck? Brainfuck is a very simple, Turing-complete programming language devised by Urban Müller in 1993. Its simplicity is remarkable: a program can be written using just eight symbols. If we were to express it in a C-like way, it would look like this: Symbol Meaning > ++ptr +++++++>++++++++++>+++>+. Dig into the C# Type System I’ll give a quick, high-level look at the main parts of the C# type system that I used to build this compiler. Generics The C# type system is built on .NET, and .NET actually instantiates generic types. In other words, generic parameters aren’t just erased; the runtime specializes code for each parameter. For example: class Foo { public void Print() => Console.WriteLine(default(T)?.ToString() ?? "null"); } new Foo().Print() prints 0, new Foo().Print() prints 0001-01-01T00:00:00, new Foo().Print() prints null. Moreover, since .NET’s generics specialize code at runtime for each type, you can rest easy with code like this: class Calculator where T : IAdditionOperators { public T Add(T left, T right) { return left + right; } } Looking at godbolt, you can see that machine code optimized for each type is generated: Calculator`1[int]:Add(int,int):int:this (FullOpts): lea eax, [rsi+rdx] ret Calculator`1[long]:Add(long,long):long:this (FullOpts): lea rax, [rsi+rdx] ret Calculator`1[ubyte]:Add(ubyte,ubyte):ubyte:this (FullOpts): add edx, esi movzx rax, dl ret Calculator`1[float]:Add(float,float):float:this (FullOpts): vaddss xmm0, xmm0, xmm1 ret Calculator`1[double]:Add(double,double):double:this (FullOpts): vaddsd xmm0, xmm0, xmm1 ret That way, if you give it different types, code specialized for each one is generated automatically. Static Abstract Members in Interfaces You might wonder how Calculator can simply add left and right within the method. That’s because .NET supports static abstract members in interfaces. For instance, IAdditionOperators is defined roughly like this: interface IAdditionOperators { abstract static TResult operator+(TSelf self, TOther other); } And by specifying where T : IAdditionOperators, the generic code can directly call operator+ on T. How’s Performance? With the above knowledge, you might want to see how well the .NET compiler can optimize when using the type system. Let’s take int (32 bits) as an example—something we’ll need for the Brainfuck compiler. If you represent a 32-bit integer as eight hexadecimal digits, each digit can be a type, and you can combine those eight digits into one type representing the entire number. First, define an interface for a hexadecimal digit: interface IHex { abstract static int Value { get; } } For example, the hex digits 0, 6, and C can be represented as: struct Hex0 : IHex { public static int Value => 0; } struct Hex6 : IHex { public static int Value => 6; } struct HexC : IHex { public static int Value => 12; } To distinguish between a “digit” and a full “number,” let’s define another generic interface INum and use an Int struct to implement it. (The idea is that in the future, it might be extended to support floating-point, etc.) interface INum { abstract static T Value { get; } } struct Int : INum where H7 : IHex where H6 : IHex where H5 : IHex where H4 : IHex where H3 : IHex where H2 : IHex where H1 : IHex where H0 : IHex { public static int Value { [MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)] get => H7.Value ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++> +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ .>. This program places each character of “Hello World!” into successive cells moving from left to right, then moves the pointer back to the start and prints them all. Still, “Hello World!” is pretty long, so here’s a simpler example that just prints 123: +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ > ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ > +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ .>. This program sets the ASCII codes for 1, 2, and 3 in consecutive cells, moves the pointer back to the first cell, and then outputs them in order. In terms of types, it looks like this: AddData (For simplicity, I wrote 49, 50, and 51 directly. In reality, you’d use something like Int to represent 49.) How to Run It Running it is super easy! Just write: AddData .Run(0, stackalloc byte[8], Console.OpenStandardInput(), Console.OpenStandardOutput()); And if you use a C# type alias, you can avoid typing such a huge generic each time: using Print123 = AddData; Print123.Run(0, stackalloc byte[8], Console.OpenStandardInput(), Console.Ope

What is Brainfuck?

Brainfuck is a very simple, Turing-complete programming language devised by Urban Müller in 1993.

Its simplicity is remarkable: a program can be written using just eight symbols.

If we were to express it in a C-like way, it would look like this:

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

> |

++ptr |

< |

--ptr |

+ |

++*ptr |

- |

--*ptr |

. |

putchar(*ptr) |

, |

*ptr = getchar() |

[ |

while (*ptr) { |

] |

} |

All you need is a byte array (memory) initialized to zero, a pointer to that array, and two byte streams for input and output. That’s enough to run a Brainfuck program.

Here’s an example program that outputs “Hello World!”:

++++++++++[>+++++++>++++++++++>+++>+<<<<-]

>++.>+.+++++++..+++.>++.<<+++++++++++++++.

>.+++.------.--------.>+.>.

Dig into the C# Type System

I’ll give a quick, high-level look at the main parts of the C# type system that I used to build this compiler.

Generics

The C# type system is built on .NET, and .NET actually instantiates generic types. In other words, generic parameters aren’t just erased; the runtime specializes code for each parameter.

For example:

class Foo<T>

{

public void Print() => Console.WriteLine(default(T)?.ToString() ?? "null");

}

-

new Fooprints().Print() 0, -

new Fooprints().Print() 0001-01-01T00:00:00, -

new Fooprints().Print() null.

Moreover, since .NET’s generics specialize code at runtime for each type, you can rest easy with code like this:

class Calculator<T> where T : IAdditionOperators<T, T, T>

{

public T Add(T left, T right)

{

return left + right;

}

}

Looking at godbolt, you can see that machine code optimized for each type is generated:

Calculator`1[int]:Add(int,int):int:this (FullOpts):

lea eax, [rsi+rdx]

ret

Calculator`1[long]:Add(long,long):long:this (FullOpts):

lea rax, [rsi+rdx]

ret

Calculator`1[ubyte]:Add(ubyte,ubyte):ubyte:this (FullOpts):

add edx, esi

movzx rax, dl

ret

Calculator`1[float]:Add(float,float):float:this (FullOpts):

vaddss xmm0, xmm0, xmm1

ret

Calculator`1[double]:Add(double,double):double:this (FullOpts):

vaddsd xmm0, xmm0, xmm1

ret

That way, if you give it different types, code specialized for each one is generated automatically.

Static Abstract Members in Interfaces

You might wonder how Calculator can simply add left and right within the method. That’s because .NET supports static abstract members in interfaces. For instance, IAdditionOperators is defined roughly like this:

interface IAdditionOperators<TSelf, TOther, TResult>

{

abstract static TResult operator+(TSelf self, TOther other);

}

And by specifying where T : IAdditionOperators, the generic code can directly call operator+ on T.

How’s Performance?

With the above knowledge, you might want to see how well the .NET compiler can optimize when using the type system. Let’s take int (32 bits) as an example—something we’ll need for the Brainfuck compiler. If you represent a 32-bit integer as eight hexadecimal digits, each digit can be a type, and you can combine those eight digits into one type representing the entire number.

First, define an interface for a hexadecimal digit:

interface IHex

{

abstract static int Value { get; }

}

For example, the hex digits 0, 6, and C can be represented as:

struct Hex0 : IHex

{

public static int Value => 0;

}

struct Hex6 : IHex

{

public static int Value => 6;

}

struct HexC : IHex

{

public static int Value => 12;

}

To distinguish between a “digit” and a full “number,” let’s define another generic interface INum and use an Int struct to implement it. (The idea is that in the future, it might be extended to support floating-point, etc.)

interface INum<T>

{

abstract static T Value { get; }

}

struct Int<H7, H6, H5, H4, H3, H2, H1, H0> : INum<int>

where H7 : IHex

where H6 : IHex

where H5 : IHex

where H4 : IHex

where H3 : IHex

where H2 : IHex

where H1 : IHex

where H0 : IHex

{

public static int Value

{

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

get => H7.Value << 28

| H6.Value << 24

| H5.Value << 20

| H4.Value << 16

| H3.Value << 12

| H2.Value << 8

| H1.Value << 4

| H0.Value;

}

}

So if you want to represent the hexadecimal value 0x1234abcd, you would write:

Int<Hex1, Hex2, Hex3, Hex4, HexA, HexB, HexC, HexD>

Here, we put [MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)] on the method to strongly suggest inlining to the compiler.

Taking a look at the godbolt compile result, you can see it gets directly optimized into 0x1234ABCD:

Int`8[Hex1,Hex2,Hex3,Hex4,HexA,HexB,HexC,HexD]:get_Value():int (FullOpts):

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov eax, 0x1234ABCD

pop rbp

ret

This is a great example of “zero-overhead abstraction”!

Now that we’re confident about performance, let’s finally build our Brainfuck compiler.

Building the Brainfuck Compiler

Compiling Brainfuck typically involves two main steps:

- Parsing the Brainfuck source code.

- Generating the compilation result.

Parsing is straightforward: scan the code from left to right and handle each command. We won’t go into detail on that here. Instead, we’ll focus on how we generate the compiled result.

In this project, we represent the program itself as a type. In other words, the compiled result is literally a type.

Basic Operations

Brainfuck needs four fundamental operations:

- Pointer movement

- Memory manipulation

- Input

- Output

To abstract these, we define an interface for operations:

interface IOp

{

abstract static int Run(int address, Span<byte> memory, Stream input, Stream output);

}

Then we make each operation into a type.

Pointer Movement

Pointer movement can be handled by a type parameter Offset (how far to move) and Next (the next operation):

struct AddPointer<Offset, Next> : IOp

where Offset : INum<int>

where Next : IOp

{

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

public static int Run(int address, Span<byte> memory, Stream input, Stream output)

{

return Next.Run(address + Offset.Value, memory, input, output);

}

}

Memory Manipulation

Next, manipulating data at the pointer:

struct AddData<Data, Next> : IOp

where Data : INum<int>

where Next : IOp

{

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

public static int Run(int address, Span<byte> memory, Stream input, Stream output)

{

memory.UnsafeAt(address) += (byte)Data.Value;

return Next.Run(address, memory, input, output);

}

}

Brainfuck typically omits memory boundary checks, so we do a little trick with an UnsafeAt extension method to avoid overhead:

internal static ref T UnsafeAt<T>(this Span<T> span, int address)

{

return ref Unsafe.Add(ref MemoryMarshal.GetReference(span), address);

}

Input and Output

Input and output are pretty straightforward:

struct OutputData<Next> : IOp

where Next : IOp

{

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

public static int Run(int address, Span<byte> memory, Stream input, Stream output)

{

output.WriteByte(memory.UnsafeAt(address));

return Next.Run(address, memory, input, output);

}

}

struct InputData<Next> : IOp

where Next : IOp

{

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

public static int Run(int address, Span<byte> memory, Stream input, Stream output)

{

var data = input.ReadByte();

if (data == -1)

{

return address;

}

memory.UnsafeAt(address) = (byte)data;

return Next.Run(address, memory, input, output);

}

}

Control Flow

Besides the basic operations, Brainfuck also needs control flow. In the end, a program needs to stop, so let’s create an operation that does nothing (Stop):

struct Stop : IOp

{

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

public static int Run(int address, Span<byte> memory, Stream input, Stream output)

{

return address;

}

}

Brainfuck loops behave like while (*ptr != 0) { ... }. So we can write:

struct Loop<Body, Next> : IOp

where Body : IOp

where Next : IOp

{

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

public static int Run(int address, Span<byte> memory, Stream input, Stream output)

{

while (memory.UnsafeAt(address) != 0)

{

address = Body.Run(address, memory, input, output);

}

return Next.Run(address, memory, input, output);

}

}

Let’s Make an Actual Program

With all these building blocks, we can represent a Brainfuck program as a C# type.

Hello World!

The well-known (to some) “Hello World!” Brainfuck code is:

++++++++++[>+++++++>++++++++++>+++>+<<<<-]

>++.>+.+++++++..+++.>++.<<+++++++++++++++.

>.+++.------.--------.>+.>.

But this code can be hard to read at first glance, so I rewrote it in a more “intuitive” way:

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++>

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++>

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++>

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++>

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++>

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++>

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++>

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++>

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++>

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++>

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++>

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

<<<<<<<<<<<

.>.>.>.>.>.>.>.>.>.>.>.

This program places each character of “Hello World!” into successive cells moving from left to right, then moves the pointer back to the start and prints them all.

Still, “Hello World!” is pretty long, so here’s a simpler example that just prints 123:

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

>

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

>

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

<<

.>.>.

This program sets the ASCII codes for 1, 2, and 3 in consecutive cells, moves the pointer back to the first cell, and then outputs them in order.

In terms of types, it looks like this:

AddData<49, AddPointer<1, AddData<50, AddPointer<1, AddData<51, // each sets the bytes for '1', '2', '3'

AddPointer<-2, // move pointer back to the start

OutputData<AddPointer<1, OutputData<AddPointer<1, OutputData< // output

Stop>>>>>>>>>>>

(For simplicity, I wrote 49, 50, and 51 directly. In reality, you’d use something like Int to represent 49.)

How to Run It

Running it is super easy! Just write:

AddData<49, AddPointer<1, AddData<50, AddPointer<1, AddData<51, AddPointer<-2, OutputData<AddPointer<1, OutputData<AddPointer<1, OutputData<Stop>>>>>>>>>>>

.Run(0, stackalloc byte[8], Console.OpenStandardInput(), Console.OpenStandardOutput());

And if you use a C# type alias, you can avoid typing such a huge generic each time:

using Print123 = AddData<49, AddPointer<1, AddData<50, AddPointer<1, AddData<51, AddPointer<-2, OutputData<AddPointer<1, OutputData<AddPointer<1, OutputData<Stop>>>>>>>>>>>;

Print123.Run(0, stackalloc byte[8], Console.OpenStandardInput(), Console.OpenStandardOutput());

On godbolt, the generated machine code looks like this:

push rbp

push r15

push r14

push r13

push rbx

lea rbp, [rsp+0x20]

mov rbx, rsi

mov r15, r8

movsxd rsi, edi

add rsi, rbx

add byte ptr [rsi], 49 ; '1'

inc edi

movsxd rsi, edi

add rsi, rbx

add byte ptr [rsi], 50 ; '2'

inc edi

movsxd rsi, edi

add rsi, rbx

add byte ptr [rsi], 51 ; '3'

lea r14d, [rdi-0x02]

movsxd rsi, r14d

movzx rsi, byte ptr [rbx+r14d]

mov rdi, r15

mov rax, qword ptr [r15]

mov r13, qword ptr [rax+0x68]

call [r13]System.IO.Stream:WriteByte(ubyte):this

inc r14d

movsxd rsi, r14d

movzx rsi, byte ptr [rbx+r14d]

mov rdi, r15

call [r13]System.IO.Stream:WriteByte(ubyte):this

inc r14d

movsxd rsi, r14d

movzx rsi, byte ptr [rbx+r14d]

mov rdi, r15

call [r13]System.IO.Stream:WriteByte(ubyte):this

mov eax, r14d

pop rbx

pop r13

pop r14

pop r15

pop rbp

ret

If you wrote this in C, it would be something like:

*(ptr++) = '1';

*(ptr++) = '2';

*ptr = '3';

ptr -= 2;

WriteByte(*(ptr++));

WriteByte(*(ptr++));

WriteByte(*ptr);

In other words, C#’s type-based abstractions are optimized away at runtime, leaving no extra overhead at all.

By the way, remember the “less intuitive” version of Hello World! code above?

If you compile it, you’ll get a type name that is extraordinarily long:

AddData<8, Loop<

AddPointer<1, AddData<4, Loop<

AddPointer<1, AddData<2, AddPointer<1, AddData<3, AddPointer<1, AddData<3, AddPointer<1, AddData<1, AddPointer<-4, AddData<-1, Stop>>>>>>>>>>,

AddPointer<1, AddData<1, AddPointer<1, AddData<1, AddPointer<1, AddData<-1, AddPointer<2, AddData<1,

Loop<AddPointer<-1, Stop>,

AddPointer<-1, AddData<-1, Stop>>

>>>>>>>>>

>>>,

AddPointer<2, OutputData<AddPointer<1, AddData<-3, OutputData<AddData<7, OutputData<OutputData<AddData<3, OutputData<AddPointer<2, OutputData<AddPointer<-1, AddData<-1, OutputData<AddPointer<-1, OutputData<AddData<3, OutputData<AddData<-6, OutputData<AddData<-8, OutputData<AddPointer<2, AddData<1, OutputData<AddPointer<1, AddData<2, OutputData<Stop>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

JIT Compilation

To run Brainfuck code just-in-time, you can generate the type at runtime and call its Run method via reflection. For example, creating a type that represents a number:

var type = GetNum(42);

static Type GetHex(int hex)

{

return hex switch

{

0 => typeof(Hex0),

1 => typeof(Hex1),

2 => typeof(Hex2),

3 => typeof(Hex3),

4 => typeof(Hex4),

5 => typeof(Hex5),

6 => typeof(Hex6),

7 => typeof(Hex7),

8 => typeof(Hex8),

9 => typeof(Hex9),

10 => typeof(HexA),

11 => typeof(HexB),

12 => typeof(HexC),

13 => typeof(HexD),

14 => typeof(HexE),

15 => typeof(HexF),

_ => throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException(nameof(hex)),

};

}

static Type GetNum(int num)

{

var hex0 = num & 0xF;

var hex1 = (num >> 4) & 0xF;

var hex2 = (num >> 8) & 0xF;

var hex3 = (num >> 12) & 0xF;

var hex4 = (num >> 16) & 0xF;

var hex5 = (num >> 20) & 0xF;

var hex6 = (num >> 24) & 0xF;

var hex7 = (num >> 28) & 0xF;

return typeof(Int<,,,,,,,>)

.MakeGenericType(

GetHex(hex7), GetHex(hex6), GetHex(hex5), GetHex(hex4),

GetHex(hex3), GetHex(hex2), GetHex(hex1), GetHex(hex0)

);

}

You’d do something similar for control flow, then call Run via reflection:

var run = (EntryPoint)Delegate.CreateDelegate(typeof(EntryPoint), type.GetMethod("Run")!);

run(0, memory, input, output);

delegate int EntryPoint(int address, Span<byte> memory, Stream input, Stream output);

AOT Compilation

If you prefer an AOT-compiled executable, you can just make the Brainfuck program type the entry point:

using HelloWorld = AddData<8, Loop<

AddPointer<1, AddData<4, Loop<

AddPointer<1, AddData<2, AddPointer<1, AddData<3, AddPointer<1, AddData<3, AddPointer<1, AddData<1, AddPointer<-4, AddData<-1, Stop>>>>>>>>>>,

AddPointer<1, AddData<1, AddPointer<1, AddData<1, AddPointer<1, AddData<-1, AddPointer<2, AddData<1,

Loop<AddPointer<-1, Stop>,

AddPointer<-1, AddData<-1, Stop>>

>>>>>>>>>

>>>,

AddPointer<2, OutputData<AddPointer<1, AddData<-3, OutputData<AddData<7, OutputData<OutputData<AddData<3, OutputData<AddPointer<2, OutputData<AddPointer<-1, AddData<-1, OutputData<AddPointer<-1, OutputData<AddData<3, OutputData<AddData<-6, OutputData<AddData<-8, OutputData<AddPointer<2, AddData<1, OutputData<AddPointer<1, AddData<2, OutputData<Stop>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>;

static void Main()

{

HelloWorld.Run(0, stackalloc byte[16], Console.OpenStandardInput(), Console.OpenStandardOutput());

}

Then compile with:

dotnet publish -c Release -r linux-x64 /p:PublishAot=true /p:IlcInstructionSet=native /p:OptimizationPreference=Speed

(IlcInstructionSet=native is like -march=native in C++, and OptimizationPreference=Speed is akin to -O2.)

When you run the resulting executable, it prints “Hello World!” directly.

Benchmarks

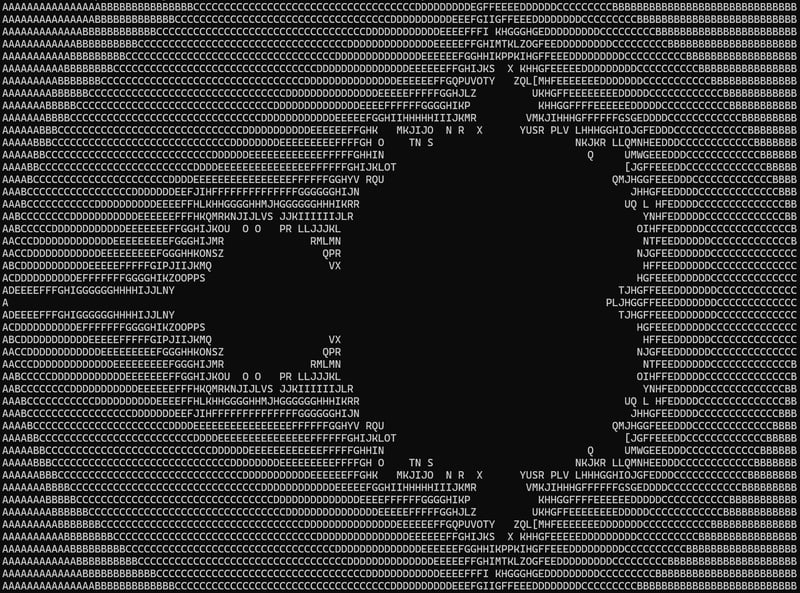

I tested performance with a Brainfuck Mandelbrot program (source on Pastebin) that draws a Mandelbrot fractal, producing something like this:

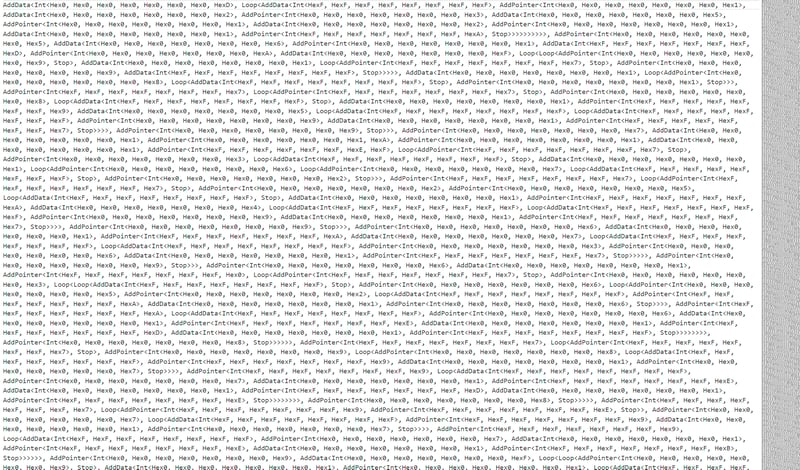

And, when converted into a type representation (with all whitespace removed), the type name is a whopping 165,425 characters long!

I ran the resulting program in five ways:

- C Interpreter A C-language Brainfuck interpreter (github link).

-

GCC

Used a Brainfuck-to-C compiler (bf2c), then compiled with

gcc -O3 -march=native. -

Clang

Similarly compiled with

clang -O3 -march=native. - .NET JIT Generated the type at runtime, then ran it (warmed up first).

- .NET AOT Used .NET NativeAOT to produce a standalone executable.

Environment:

- OS: Debian GNU/Linux 12 (bookworm)

- CPU: 13th Gen Intel® Core™ i7-13700K

- RAM: CORSAIR DDR5-6800MHz 32G×2

I ran each method 10 times and took the fastest result. All output was redirected to /dev/null to avoid slowdowns from console I/O. The results:

| Method | Time (ms) | Rank | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| C Interpreter | 4874.6587 | 5 | 5.59 |

| GCC | 901.0225 | 3 | 1.03 |

| Clang | 881.7177 | 2 | 1.01 |

| .NET JIT | 925.1596 | 4 | 1.06 |

| .NET AOT | 872.2287 | 1 | 1.00 |

Surprisingly, .NET AOT beat out C to claim first place. You could say this is all thanks to the zero-overhead abstractions the C# type system provides.

Conclusion

By leveraging the C# type system, building a Brainfuck compiler becomes more like a fun experiment rather than a daunting project. This project also proved that .NET has a flexible type system, with an advanced optimization compiler that can optimize away those abstractions to achieve high performance.

Project

The project is open sourced under MIT license: https://github.com/hez2010/Brainfly