AI and the Face of Fear – Context Adds a New Dimension

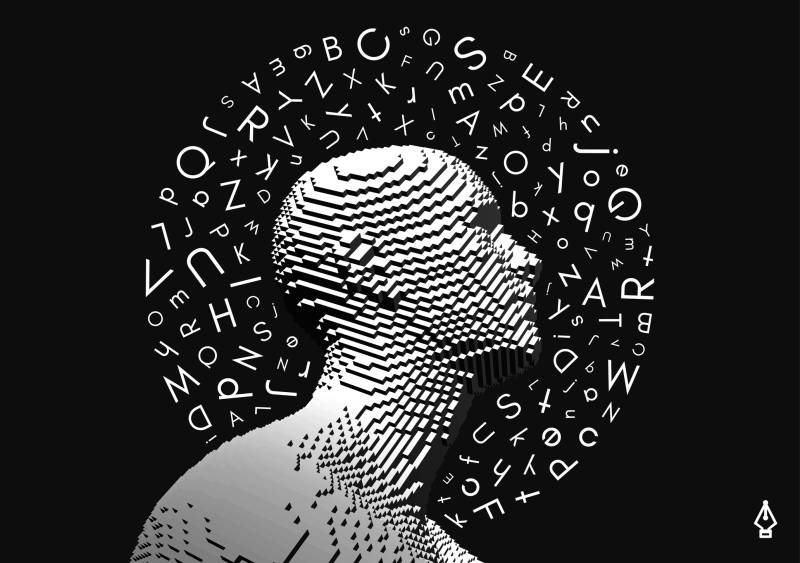

For generations, the human face has been heralded as the mirror of the soul—a canvas upon which emotions like fear are vividly painted. Think of widened eyes, a gaping mouth, or a furrowed brow, and you might imagine you’ve cracked the code of terror. Yet, a groundbreaking study from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem has turned this assumption on its head, revealing that the real key to recognising fear lies not in the face, but in the world around it. Context, it seems, reigns supreme. Led by Professor Hillel Aviezer and Ph.D. student Maya Lecker, this research, published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), challenges decades of psychological orthodoxy. Through an ambitious analysis of real-life fear responses—captured in videos of people facing heights, physical assaults, or phobia-inducing triggers—the team discovered that facial expressions alone are startlingly unreliable as indicators of fear. Instead, it’s the situational context—think body posture, environmental cues, or the sheer chaos of a moment—that delivers the true emotional punch. Decoding "Context" in Context So, what exactly do we mean by context in this, well, context? The word itself, derived from the Latin contexere ("to weave together"), refers to the circumstances or background that frame an event, giving it meaning. Here, it’s the difference between seeing a wide-eyed face in isolation and witnessing that same face atop a rickety ladder, arms flailing, with a sheer drop below (learn more about contextual learning). Context stitches together the narrative threads—visual, spatial, and temporal—that allow us to interpret what’s really happening. Aviezer’s study suggests that without this tapestry, the face is just a fragment, a riddle without a solution. This revelation isn’t merely academic navel-gazing. It has seismic implications for fields as diverse as psychology, neuroscience, and artificial intelligence (AI). Current AI emotion-detection systems—like those powering facial recognition software (explore facial recognition technology)—are often trained on posed expressions, assuming fear can be boiled down to a universal grimace. But if context is the linchpin, these algorithms are missing the bigger picture, literally and figuratively (read about AI limitations). The Experiment: Fear in the Wild To unravel this mystery, Aviezer’s team conducted 12 meticulously designed experiments, involving 4,180 participants. They sourced raw, unfiltered footage of people in genuinely terrifying scenarios—think bungee jumps or spider encounters (see real-life fear examples)—and dissected it into three viewing conditions: faces alone, context without faces, and full videos combining both. Participants then judged the emotions using various methods, from labelling to rating intensity. The findings were stark. Isolated faces? A muddled mess—participants struggled to pinpoint fear. Context alone, or context with faces? Crystal clear. Fear leapt off the screen, unmistakable and visceral (discover more about emotion perception). It’s a humbling reminder that humans are wired to read the world holistically, not in fragments. Although admittedly, AI may well very soon become far more efficient at detecting human emotion than any human, which means that in the not too distant future perhaps even the face will deliver far more data than is even required by an AI entity in order for an accurate assessment to be made. A Strange Oversight? What’s peculiar—and worth a raised eyebrow—is that scientists needed correcting on this at all. For years, research clung to the idea that fear was a facial billboard, despite everyday evidence to the contrary. After all, humans are masters of disguise. A clenched jaw or a forced smile can mask dread in a heartbeat—think of a nervous flyer chatting breezily as the plane hits turbulence (learn about masking emotions). Actors, poker players, and even children learn to cloak fear behind a façade. Surely, it’s odd that academia overlooked this chameleon-like adaptability, fixating instead on staged expressions in sterile labs (explore the history of emotion research). Perhaps the oversight stems from a love affair with simplicity. The face is a convenient focal point—measurable, photographable, and ripe for theorising. Context, by contrast, is messy, sprawling, and harder to pin down. But as this study proves, messiness is where the truth often hides (dive into complexity in science). The Road Ahead The implications ripple far beyond the lab. For psychologists, it’s a call to rethink how we study emotions, moving beyond the face to embrace the full human experience (see modern psychology trends). For neuroscientists, it raises questions about how the brain integrates contextual cues—perhaps pointing to untapped neural pathways (read about brain-emotion links). And for AI developers, it’s a wake-up call: machines won’t truly "see" us until they learn to look beyond our skin (exp

For generations, the human face has been heralded as the mirror of the soul—a canvas upon which emotions like fear are vividly painted. Think of widened eyes, a gaping mouth, or a furrowed brow, and you might imagine you’ve cracked the code of terror. Yet, a groundbreaking study from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem has turned this assumption on its head, revealing that the real key to recognising fear lies not in the face, but in the world around it. Context, it seems, reigns supreme.

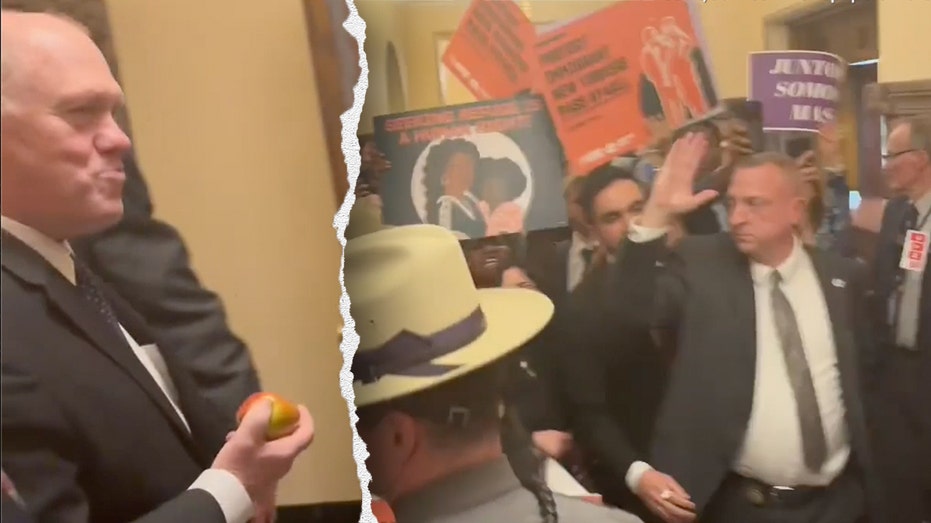

Led by Professor Hillel Aviezer and Ph.D. student Maya Lecker, this research, published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), challenges decades of psychological orthodoxy. Through an ambitious analysis of real-life fear responses—captured in videos of people facing heights, physical assaults, or phobia-inducing triggers—the team discovered that facial expressions alone are startlingly unreliable as indicators of fear. Instead, it’s the situational context—think body posture, environmental cues, or the sheer chaos of a moment—that delivers the true emotional punch.

Decoding "Context" in Context

So, what exactly do we mean by context in this, well, context? The word itself, derived from the Latin contexere ("to weave together"), refers to the circumstances or background that frame an event, giving it meaning. Here, it’s the difference between seeing a wide-eyed face in isolation and witnessing that same face atop a rickety ladder, arms flailing, with a sheer drop below (learn more about contextual learning). Context stitches together the narrative threads—visual, spatial, and temporal—that allow us to interpret what’s really happening. Aviezer’s study suggests that without this tapestry, the face is just a fragment, a riddle without a solution.

This revelation isn’t merely academic navel-gazing. It has seismic implications for fields as diverse as psychology, neuroscience, and artificial intelligence (AI). Current AI emotion-detection systems—like those powering facial recognition software (explore facial recognition technology)—are often trained on posed expressions, assuming fear can be boiled down to a universal grimace. But if context is the linchpin, these algorithms are missing the bigger picture, literally and figuratively (read about AI limitations).

The Experiment: Fear in the Wild

To unravel this mystery, Aviezer’s team conducted 12 meticulously designed experiments, involving 4,180 participants. They sourced raw, unfiltered footage of people in genuinely terrifying scenarios—think bungee jumps or spider encounters (see real-life fear examples)—and dissected it into three viewing conditions: faces alone, context without faces, and full videos combining both. Participants then judged the emotions using various methods, from labelling to rating intensity.

The findings were stark. Isolated faces? A muddled mess—participants struggled to pinpoint fear. Context alone, or context with faces? Crystal clear. Fear leapt off the screen, unmistakable and visceral (discover more about emotion perception). It’s a humbling reminder that humans are wired to read the world holistically, not in fragments. Although admittedly, AI may well very soon become far more efficient at detecting human emotion than any human, which means that in the not too distant future perhaps even the face will deliver far more data than is even required by an AI entity in order for an accurate assessment to be made.

A Strange Oversight?

What’s peculiar—and worth a raised eyebrow—is that scientists needed correcting on this at all. For years, research clung to the idea that fear was a facial billboard, despite everyday evidence to the contrary. After all, humans are masters of disguise. A clenched jaw or a forced smile can mask dread in a heartbeat—think of a nervous flyer chatting breezily as the plane hits turbulence (learn about masking emotions). Actors, poker players, and even children learn to cloak fear behind a façade. Surely, it’s odd that academia overlooked this chameleon-like adaptability, fixating instead on staged expressions in sterile labs (explore the history of emotion research).

Perhaps the oversight stems from a love affair with simplicity. The face is a convenient focal point—measurable, photographable, and ripe for theorising. Context, by contrast, is messy, sprawling, and harder to pin down. But as this study proves, messiness is where the truth often hides (dive into complexity in science).

The Road Ahead

The implications ripple far beyond the lab. For psychologists, it’s a call to rethink how we study emotions, moving beyond the face to embrace the full human experience (see modern psychology trends). For neuroscientists, it raises questions about how the brain integrates contextual cues—perhaps pointing to untapped neural pathways (read about brain-emotion links). And for AI developers, it’s a wake-up call: machines won’t truly "see" us until they learn to look beyond our skin (explore AI’s future).

As Professor Aviezer puts it, “Real-life fear reactions tell a different story.” It’s a story written not in fleeting grimaces, but in the trembling hands, the looming shadows, and the silent screams of circumstance. Fear, it turns out, isn’t just a face—it’s a world. And until we—and our machines—learn to read that world, we’ll only ever see half the picture.

.webp?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)