A judicial doctrine favored by conservatives could stymie Trump

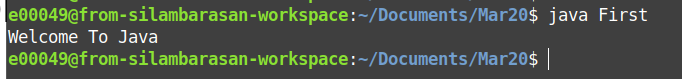

The constitutional significance of the non-delegation doctrine emerged during the early part of the 20th century with the New Deal and the rise of the regulatory state.

The beginning of the second Trump presidency has been marked by the unilateral use of executive orders to restructure the federal government and change policy. These actions have been met with near silence from a Republican Congress.

Partisanship, narrow majorities and personal loyalty to Trump may all explain this. Some see Congress as ceding so much power that it has abdicated its constitutional duties to provide checks and balances and the separation of powers. This ceding of power — either expressly by legislation or implicitly by inaction — could create a constitutional dilemma, leaving some Americans hoping that the judiciary will serve as a check on the administration.

The federal courts have already stayed many Trump initiatives. Among the tools that the judiciary may turn to is a revitalization of the “non-delegation doctrine,” which states that “Congress cannot delegate its legislative powers or lawmaking ability to other entities. This prohibition typically involves Congress delegating its powers to administrative agencies or to private organizations.”

The doctrine is rooted in Article I, Section One of the Constitution, which vests the legislative power in the House and Senate. Making laws, along with functions such as appropriating money, are inherently legislative functions that Congress may not give away to another branch of government or to a private entity.

The constitutional significance of the non-delegation doctrine emerged during the early part of the 20th century with the New Deal and the rise of the regulatory state. As Congress created regulatory agencies — such as the Food and Drug Administration, the Securities and Exchange Commission and Federal Trade Commission — it delegated to them broad authority to determine what is a safe drug, securities fraud or unfair competition. In effect, it gave these agencies broad authority to issue administrative rules that carried the force of law.

In 1928, the Supreme Court drew a limit on that delegation in J.W. Hampton v. United States. It held that delegation was permissible so long as there was an “intelligible” limit to the discretion that the administrative agency employed. Congress could not pass a law giving executive branch entities, including the president, unlimited discretion to make law or policy. For example, it could not adopt a law that said, “Congress is transferring its lawmaking power to the executive branch.”

The most famous case invoking the non-delegation doctrine was 1935's Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, wherein the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional an act that delegated to private groups via the executive branch the authority to make rules of fair business competition. Here the non-delegation doctrine was used to strike down parts of what was referred to as the First New Deal regulations.

Yet since Schechter, the Supreme Court has never again used non-delegation to strike down legislation. Some speculate that perhaps Congress has learned its lesson and avoided violating the intelligible principle, whereas others argue that the court has simply abandoned it.

In cases such as Mistretta v. United States, Whitman v. American Trucking Association and United States v. Mead, the court saw congressional delegation of power as pushing the limits of the non-delegation doctrine but not crossing it. Even in Trump v. Hawaii, wherein Trump issued the so-called “Muslim travel ban,” the court debated whether the president had crossed the line, but ultimately ruled that he had not.

Yet in 2019’s Gundy v. United States, four of the justices (Roberts, Thomas, Gorsuch and Alito) argued for a strengthening and rethinking of the non-delegation doctrine because of their concern that Congress has ceded too much authority to administrative and executive agencies. Conservatives have long called for the doctrine to be given a new life. This renewed support for the delegation doctrine and limits on administrative agency discretion is also evident in the recent Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo decision, which overturned Chevron deference.

As the battle over the constitutionality of Trump’s actions turn to the courts, it would not be a surprise if a conservative Supreme Court or lower federal court judges look to the non-delegation doctrine as a tool to check executive branch authority.

David Schultz is a Distinguished University Professor and the Winston Folkers Endowed Distinguished Faculty Chair in political science at Hamline University.