10 Great Western Movie Classics You Probably Haven’t Seen

The Western genre has been integral to cinema since its early days, with its iconic imagery of vast, open landscapes, shootouts at high noon, and larger-than-life characters. However, for every The Searchers (1956) or Unforgiven (1992), there are lesser-known gems that quietly go unnoticed but deserve to be discovered. Although these films may never have […]

The Western genre has been integral to cinema since its early days, with its iconic imagery of vast, open landscapes, shootouts at high noon, and larger-than-life characters. However, for every The Searchers (1956) or Unforgiven (1992), there are lesser-known gems that quietly go unnoticed but deserve to be discovered. Although these films may never have found the right audience or have somehow fallen by the wayside, these films stand as testaments to the versatility and enduring appeal of the genre.

This collection of Westerns—five pre-1970 and five post—shows the breadth of the genre’s emotional and thematic reach and proves that there’s far more to the Western than just cowboy standoffs.

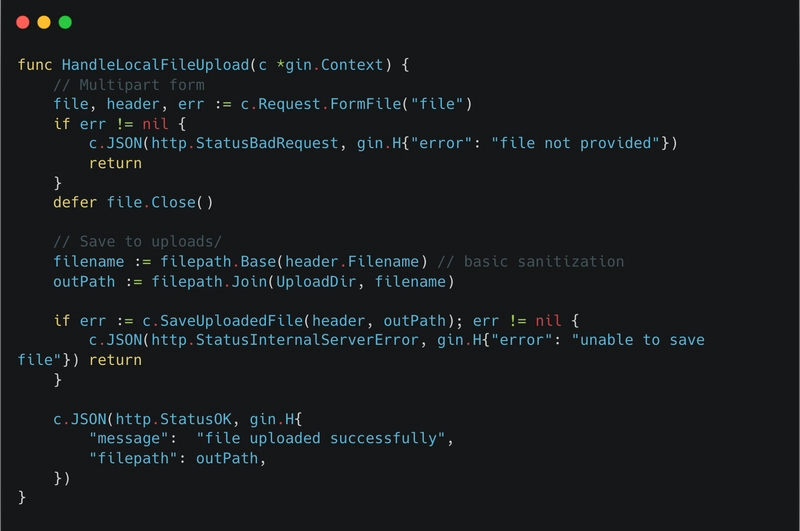

1. Western Union (1941)

Directed by Fritz Lang, Western Union is a beautifully crafted, though often overlooked Western that strays from the expected frontier clichés. Although perhaps more well known for his German expressionist masterpieces Metropolis (1927) and M (1931) amongst others, Western Union proves that Lang had even more strings to his bow than you may have thought.

It’s not a film that would typically come to mind when thinking of classic Westerns, but it strikes a fascinating balance between the traditional and the modern, reflecting the shift in American society at the time.

Western Union sees the legendary Randolph Scott playing Vance Shaw, a reformed outlaw enlisted to help build the telegraph line across the American frontier. Lang brings a nuanced and somewhat noirish sensibility to the Western, perhaps unsurprising when you consider his more well known output, and the moral dilemmas faced by Shaw are more complex than the usual battle between good and evil, especially as he grapples with his past as an outlaw while working for a cause that represents the future.

There are also subtle nods to works like Metropolis with Western Union addressing themes of progress and technology, and Lang’s trademark visual style—the striking use of shadows, light, and framing—adds an almost existential weight to the proceedings. The expansive American landscape is shot in vivid colour, and at a time when the world was still very much coming to terms with that cinematic medium. It shouldn’t be a surprise that Lang was at the forefront of such a work, it’s just a shame it’s not held up in as high regard as some of his other films.

2. Canyon Passage (1946)

Jacques Tourneur is best known for his work in the horror genre, particularly Cat People (1942) and Out of the Past (1947), but Canyon Passage demonstrates his ability to weave psychological complexity into the Western genre.

Set in 1850s Oregon, the film tells the story of Logan Stuart (a terrific Dana Andrews), a freight company owner whose romantic escapades and involvement in the local politics of a frontier town pull him into a web of intrigue and danger.

What makes Canyon Passage unique is the way it focuses on the emotional and psychological lives of its characters and doesn’t simply shower the audience in shootouts or overblown set pieces. Tourneur digs deeper into the complexities of human relationships and the way the frontier shaped the people who lived within it. Logan’s inner demons frequently become the center of the piece as he grapples with his own choices whilst struggling with the various mishaps that he’s become a part of.

The sweeping vistas of the Oregon wilderness are as much a part of the story as the characters themselves, creating an atmosphere that is at once captivating and melancholic. Canyon Passage is an intelligent, emotionally layered Western that has often been overlooked but remains an essential part of the genre’s history, also skilfully threading political elements into its brief, yet effective, run time.

3. Rawhide (1951)

At first glance, Rawhide might seem like just another 1950s Western, but it stands out for its taut, almost noir-like structure and its focus on human psychology under pressure. The film takes place at a remote stagecoach relay station, where Tyrone Power plays the station master, and Susan Hayward portrays a traveller caught up in the tension when a gang of escaped convicts takes over the station.

It’s not the first or last time we see a siege in a Western, but Rawhide’s drama unfolds in its dialogue and moral indistinctness, with the claustrophobic set up forcing characters to us their brains rather than brawn to somehow detach themselves from the horror unfolding.

Hayward’s performance especially is terrific—her portrayal of a woman who must quickly adapt to a dire situation is both strong and nuanced. She is more than just a damsel in distress; instead, she’s a fully realised character who forces the men around her to rethink their roles in this tense drama, arguably not something we’re accustomed to from the era.

Rawhide may not break new ground in the genre, but it executes its simple premise with exceptional skill, drawing viewers into its intense, claustrophobic atmosphere, and laid down a marker for things to come.

4. The Hanging Tree (1959)

Robert Wise and Delmer Davis’ film is a rare beast within the genre in that it lingers long after the credits role. On the surface it qualifies as a Western for sure; there’s a gold rush town, saloons, naturally a gunslinger or two, but The Hanging Tree has plenty to discover beneath its seemingly standard surface.

Cooper plays Dr. Joseph Frail, a haunted physician who arrives in a rough Montana gold camp with a gun, a past, and a rigid moral code. When he saves a young man (Ben Piazza) from a mob, and takes in a wounded woman (Maria Schell), his self-imposed exile begins to crack.

The script (co-written by the infamous, and at the time blacklisted, Dalton Trumbo, under a pseudonym) is deceptively tight, slow-burning, and weirdly psychological. There’s a gothic-like undercurrent running through the film—jealousy, obsession, control—and the tone never quite lets you relax. It’s a Western but one that’s frequently at odds with its own classic genre.

The Hanging Tree is underseen, underrated—and at times, kind of brilliant.

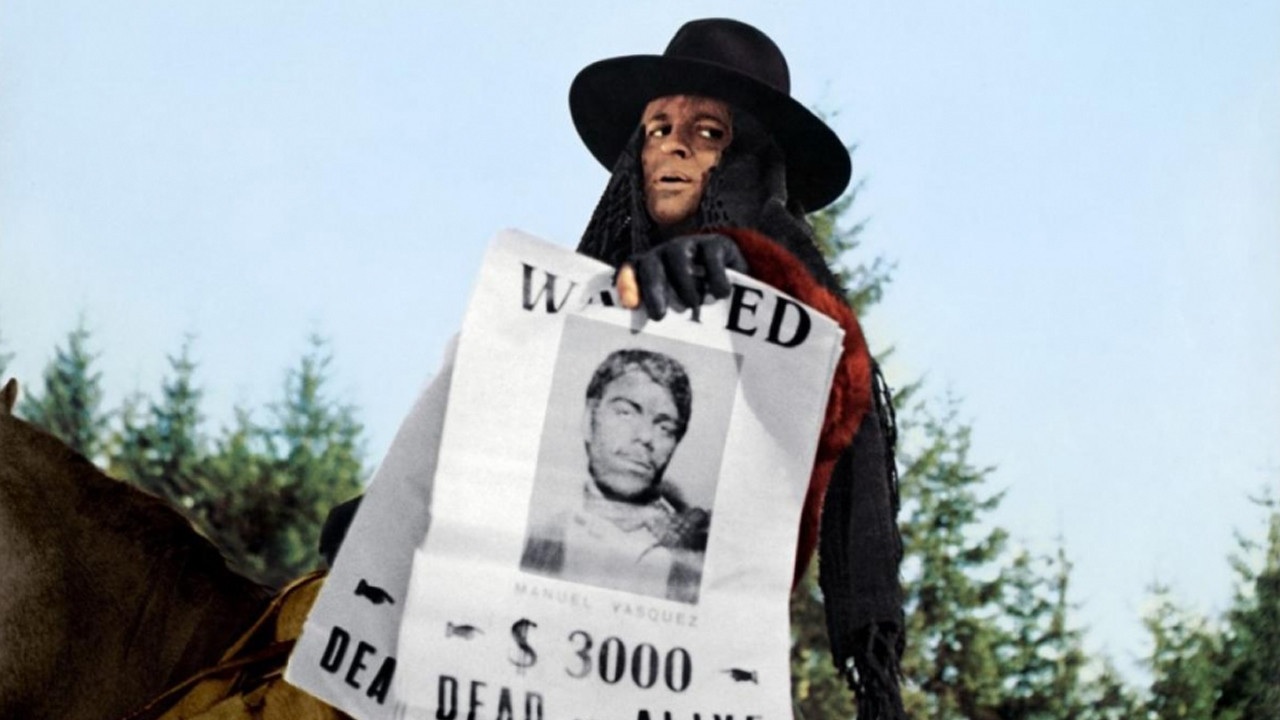

5. The Great Silence (1968)

Arguably one of the most radical and bleak Westerns ever made, The Great Silence (1968) is a masterpiece of nihilism and despair. Directed by Sergio Corbucci, this film features Jean-Louis Trintignant as a mute gunslinger who must face off against a sadistic bounty hunter played by Klaus Kinski, and thankfully Werner Herzog is nowhere in sight.

Set in a snow-covered frontier town, the film emits a coldness that permeates not just the landscape but the hearts of its characters. Trintignant’s character is more ambiguous—silent, withdrawn, and marked by a tragic past. The Great Silence is well titled, dealing in themes of isolation, moral torpor and leading to the ultimate subversion of the classic Western ending, revolutionary for its time, and a comment upon the futility of the concept of revenge.